Jason Reynolds

Imagination and Fortitude

Jason Reynolds is the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature of the Library of Congress — and a magnificent source of wisdom for human society as a whole. He’s driven by compassion and the clear-eyed honesty that the young both possess and demand of the rest of us. Ibram X. Kendi chose him to write the YA companion to Stamped from the Beginning. In his person, Jason Reynolds both embodies and inspires innate human powers of fortitude and imagination. Hear him on “breathlaughter”; the libraries in all of our heads; and a stunning working definition of anti-racism: “simply the muscle that says humans are human… I love you, because you remind me more of myself than not.”

Image by Nathan Bajar, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Jason Reynolds was appointed National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature by the Library of Congress in January 2020. His body of writing about what it is to be a Black young person growing up in the U.S. has been received as a godsend by teachers and librarians — including the award-winning Ghost, Long Way Down, and Look Both Ways. His most recent work of nonfiction, together with Ibram X. Kendi, is Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: We all know that the best writers for children and young adults speak profoundly to people of every age. I first became aware of and interviewed Jason Reynolds, the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature of the Library of Congress, in 2020. I have come to see him as a magnificent presence and source of wisdom for present human society as a whole. He’s as driven by compassion as he is committed to the clear-eyed honesty that the young both possess and demand of the rest of us. His body of books about what it is to be a Black boy, a Black young person growing up in the U.S., have been received as a godsend by teachers and librarians. And in his person, he lifts up innate human powers of fortitude and imagination. He offers gifts of wisdom and practice, like “breathlaughter” and the libraries in our heads, and a stunning working definition of what anti-racism actually means.

Reynolds: Anti-racism is simply the muscle that says that humans are human. That’s it. It’s the one that says, “I love you because you are you.” Period. And if we can figure out how to do that — and it feels so simple. And this is why racism has been the greatest hoax ever played on humans. It’s the greatest hoax ever, because that element of “I love you because you are you” should be the most human thing we know. It should be a natural thing to say, “Look, I love you, because you remind me more of myself than not.”

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Jason Reynolds’ many books for middle grade and young adult readers include Ghost, Long Way Down, Look Both Ways, and, most recently, Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You. He was born in Washington D.C. in 1983.

As you may or may not recall, we got connected on Twitter by a guy named Danté Stewart, a young man who’s a Black seminarian and pastor and preacher, and really a wonderful writer. And he’s a bit younger than you, he’s in his 20s, but he said that he picked up Ghost just a couple of years ago and was immediately drawn by the way you told stories that intersected themes of race, community, social change, failure, insecurity, etc. He said, “It was the story of my life.” So I guess I want to ask you, what was it like to be Jason, growing up? How did this all manifest? What’s with you as you think of, as you walk through these days, about how you started walking in your body as a child?

Reynolds: I think young Jason is always thinking of my mother. I was raised by a fascinating woman. And there were certain things that we learned in the house that molded me. For instance, my mother had no problem saying that, even if it was an ancient belief system, that she had no problem saying, “It doesn’t make sense, so we don’t have to believe that.” [laughs] When you’re a kid, you’re like, “Mom, everyone is telling me that my friends who are gay aren’t going to go to heaven.” You’re a kid, and that’s scary. And my mom was like, “Oh, that’s not true.” [laughs] And for her, it was like, that’s not true, because it doesn’t make sense. So as a kid, that was all very normal in my house. And it was secretive. My mom would always say, “Look, don’t tell people what we doing in here. The way I’m raising you up might not be up to standard.”

Tippett: [laughs] So you had to keep it a secret.

Reynolds: I had to keep it a secret. I had to keep it a secret. And so when I discovered language at the age of ten, through rap music — because I wasn’t a reader. That wasn’t a thing in our house. It’s interesting, my mother, as brilliant as she was and as progressive as she was, she also was a mom raising kids, working long hours and doing all the things that a lot of us have to do, and so reading just wasn’t something that was modeled in our home. And it wasn’t —

Tippett: Somewhere, Ibram X. Kendi, who you wrote this book Stamped with — we’re going to talk about this, but he wrote, he said, “Jason Reynolds and I avoided books like we avoided police officers, growing up in the 1990s.”

Reynolds: It’s true, no books for me. I mean, and why would I read books, honestly, back in those days? I think — you have the wave, the height of the crack epidemic that’s happening in the last ’80s, early ’90s. Hip-hop is being used as a way to actually fight against it. It’s in response to it, so much of it. The other part of that convergence, that triangulation, was what we now know as HIV and AIDS. Two of my neighbors died of AIDS on my block. I had family members who were addicted to crack cocaine during that time. I have an older brother who all he was doing was listening to rap music. All of this is happening, and there’s a ten-year-old child in the middle of it, and there are no books about any of it. And so reading just wasn’t my jam. It wasn’t for me. So I studied rap lyrics, liner notes. I would open up cassette tapes, and I would unfold the liner notes, and I would read what the rappers were rapping.

Tippett: Which is poetry. Rap lyrics are poetry.

Reynolds: Thank you for saying it.

Tippett: So you were reading poetry.

Reynolds: I was reading poetry. And that’s all it took. I didn’t want to be a rapper, I wanted to be a poet. I wanted to write it down. And that was sort of the beginning of all this. And so when you combine that with my mother’s pouring into us that, look, you can say whatever you want to say, you can feel however you want to feel, you can research and study whatever you want to research and study, you can believe whatever you want to believe, this gave me the platform to put forth my young, curious ideas, as a 10-, 11-, 12-year-old.

Tippett: It’s interesting, I was looking at Kojo Nnamdi, who’s such a great…

Reynolds: Oh, he’s awesome.

Tippett: … public radio host in D.C., who interviewed you actually not that long ago — early June?

Reynolds: Oh, yeah, all the time.

Tippett: I mean, I’m sure he’s interviewed you a lot.

Reynolds: Last week.

Tippett: Last week, with kids, with your readers. But — and I don’t know if it was in this context or another, but there was a librarian in D.C. — maybe this was something written about you, talking about how before your books came along, what she was doing with kids in her library was analyzing rap lyrics.

Reynolds: That’s the way.

Tippett: To listen to that show, where kids called in to name their questions with you — “I’m scared of being a Black person. What should I do?” “Why do people still hurt Black people?” “I’m nine years old. My question is, I’m scared. How can kids help bring change in this country, so we’re all treated fairly and it doesn’t matter what color your skin is?” I just wanted to put those questions out there and name that that’s what you’re writing into or toward, for.

Reynolds: Krista, it’s been — I wish I could tell you that that was the first time I’ve heard those questions. But the truth is that I’ve been doing this work a long time — at this point, I’ve spoken to probably a million kids around this country and parts of the world — and those questions come. I’ve had a little girl in Philly, so sweet, and she made me bend down so she can whisper in my ear, do I ever wish that my skin was different?, because of what she felt, what she was dealing with. Or I’ve had young people tell me about their brothers and sisters being killed by police officers, or — I mean, this is very real.

And my job is to love them. And if I claim to love them — because all of us claim to love our kids, but I think sometimes, our love sometimes gets conflated with our fear. And that’s OK — I understand that fear is real. But for me, my own personal opinion is that if I love them, I have to tell them the truth. I have to figure out how to tell them the truth: one, because a lot of these kids can handle it. I think we spend so much time trying to protect our children that we —

Tippett: Also, because they see it.

Reynolds: They see it.

Tippett: They see it. They know it. And this is true of kids altogether, everything that’s going on that adults think they’re shielding them from.

Reynolds: But they’re not. They know. And so if they know, and we’re not helping them process, now it’s become more dangerous than you’ve ever imagined. So we have an opportunity to lean into the discomfort of having to talk to kids about this, in order for them to find language around it. And honestly, I don’t want — I always tell young people, racism is nothing to make sense of. That’s the complicated part about it. [laughs] That’s why it’s such a strange conversation. It’s nothing to make sense of. But we do have to lean into having a discussion about how nonsensical it is.

Tippett: I think that language of helping kids process — one place, you said you don’t write pain porn or trauma porn. And boy, we are addicted to that stuff in this society, like true crime. But the stories you tell have a lot of pain in them, and they have a lot of trauma in them. I wonder, how would you talk about that line? What are the different ingredients that go into that line between telling the hard, true stories?

Reynolds: I think, for me — look, trauma is real. Pain is real. But it is not omnipresent. It isn’t something that governs my life, and it especially doesn’t govern the lives of children. I think it is disingenuous to write it. I think it’s hack work, because the truth is that if you know children, children — who are the most human amongst us, by the way — children always find a way to laugh. Children always find a way. If you’re talking to a 14-year-old, no matter what’s going on, a 14-year-old is trying to figure out where the joke is. They’re trying to figure out when the opportunity comes for the sad part to be over so that they can roast their best friends.

I think that the fervent nature of finding humor and lightness and levity is a remarkable gift of youth, honestly. And so for me, I’m not interested — look, I write that which I believe is real and things that happen, and I don’t want to shy away from things that are complicated and tough, but I also want to write whole stories about whole people. I think sometimes we reduce children and young people to half-formed things, and so we write half-formed stories about them.

And even that ties to the way people talk about children’s literature. People talk about children’s literature as if it is a category that is full of half-formed work, but that’s because they too believe that children are half-formed. [laughs] And so I think those of us who acknowledge the humanity of young people, those of us who acknowledge the complexity and the beauty and sophistication of childhood know that when you’re writing it, all those elements have to be present.

Tippett: I want to talk about some of the ways that you get at this, because I think these are important tools for all the rest of us — and parents and teachers, but all of us. You talk about using synonyms when you’re helping kids process and letting them come up with synonyms. And one that I was so intrigued by that you used is a made-up synonym for “freedom,” is — this is one word — “breathlaughter.”

Reynolds: Breathlaughter, yeah. Oh, it sounds good, doesn’t it? [laughs] I think, for me — look, my whole life is around figuring out — is playing around with the alchemy of language. That’s my whole jam. I want to figure, what exactly are the chemical reactions that take place when you put this word next to this word? That’s something that — I think about the poet John Ashbery, that was his whole thing. It’s like, I don’t know what this means, but if you put these two words together, what does it make you feel? And I’m curious about that.

So you take something like freedom. What could be a synonym for freedom? And I made up the word breathlaughter, because there’s something about the idea, for me, that — when I think of breath, I think of life, but I also think of, it doesn’t stop. So if you exhale, what comes out of your mouth spreads and spreads and spreads. It goes and goes and goes and goes. And that’s something to think about. It’s something to think about, what happens when we breathe out or breathe in. It’s also interesting to think about that we’re breathing in, and then breathing out, which means it’s a constant recycling of energy. What an amazing thing to think about, just constant recycling of energy.

And so what if laughter could also be recycled in that way? What if it could just go? That is freedom, to me, if it could just go and go and go and go and go — if it could be the ripple in the water. To me, that feels free. Now, physically free, that’s a different conversation. But that feels like freedom to me, so yeah.

[music: “I’m 9 Today” by múm]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today I’m with Jason Reynolds, the celebrated young writer of books for middle schoolers and young adults, with wisdom for all humans.

[music: “I’m 9 Today” by múm]

Something I really appreciate in your work, in your philosophy of writing, in what you write, is a reverence you have for the power of words and ideas. I grew up in the middle of the country — this is not related to race — this is a very American thing, this anti-intellectualism, this mistrusting of the life of the mind. And so I watched this — what’s your title? You are the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature of the Library of Congress — what a fabulous title. I watched you give a speech — was it for the Library of Congress or librarians? And you talked about libraries as sacred spaces and librarians as architects, and what if libraries are warehouses where we build human libraries and that the questions kids have get stored on the shelves and passed around and loaned out to others? [laughs] And you talked about the reference desks we have in our heads. And this piece of it that you’re calling out — it is, it’s countercultural in a strange way that we don’t reflect on in American culture and feels really essential, to me. Do you know what I’m talking about?

Reynolds: I do. I do. I think — and that’s interesting, because no one ever talks about that speech, because I — ultimately, I think that my role, for as long as I am on this plane and as long as I am doing this work, my role will always be to figure out how to create fortitude in the minds and bodies and spirits of young people. I’m trying to fortify them. It’s also the reason why I do so much around imagination — this is a big deal for me — or why I do the whole “let’s create synonyms,” because at the end of the day, ultimately, I need young people — we, the collective we need young people to be able to activate their imaginations. If they cannot, if they don’t have — if, by the time you’re out of high school, your imagination is shot, we’re in trouble, bigtime. We’re in trouble.

But how does one keep an imagination fresh in a world that works double-time to suck it away? How does one keep an imagination firing off when we live in a nation that is constantly vacuuming it from them? And I think that the answer is, one must live a curious life. One must have stacks and stacks and stacks of books on the inside of their bodies. And those books don’t have to be the things that you’ve read. I mean, that’s good, too, but those books could be the conversations that you’ve had with your friends that are unlike the conversations you were having last week. It could be about this time taking the long way home and seeing what’s around you that you’ve never seen, because most of us, especially city folk, we stay in our little quadrants. We stay on the five-block radius, wherever the coffeeshop is and the school and the church.

But what if you were to walk the other way? What if you were to explore the places around you? What if you were to speak to your neighbor and to figure out how to strike a conversation with a person you’ve never met? What if you were to try to walk into a situation, free of preconceived notion, just once? Once a day, just walk in and say, “I don’t know what’s going to happen, and let’s see. Let me give this person the benefit of the doubt — to be a human.”

Tippett: Well, can I just say one thing about that? I was just thinking recently about the word “repentance” — I just think you might like this, because you like words — that repentance, in the Greek and the Hebrew, it is not about a private conversion. The word is kinetic. The word actually is about stopping in your tracks and walking another way, which is what you just described as a way to talk about — I think in some ways the way you said it is very simple, in the sense that it’s very manageable, like stepping out of our neighborhoods.

Reynolds: That’s it. [laughs] But isn’t that the thing? This is also why I work with young people and why I love young people, is because they haven’t complicated life yet. If you ask a young person, “What advice would you give a white person right now, in the midst of all the things that are happening?” And that young person, especially a young Black person, would say, “Oh, ‘Stop being racist.’”

Tippett: [laughs] Right.

Reynolds: [laughs] Right? Because for them, it’s very much so, why are we complicating this conversation? Let’s figure out whatever — the shortest distance between A and B is a straight line, so let’s just do the straight-line way and say, “Here’s what you could do. Stop being racist right now. It’s on you to figure out what that means, but that’s the answer.” [laughs]

Tippett: It’s like Oliver Wendell Holmes: “the simplicity that lies on the other side of complexity.”

Reynolds: [laughs] That’s what I’m searching for, what I’m trying to push for. Just step out your neighborhood. Just talk to somebody different, because we underestimate what this does for the mind. That’s all. We underestimate what it does for the imagination. And as long as those imaginations are firing off, then their libraries will continue to be filled.

Somebody told me at that same lecture — it cuts off when you watch it on the internet, but at the same lecture, when we got to the Q&A part, a woman stood up and she said, “Have you ever been to Senegal?” And I said no. And she said, “Do you know any Senegalese people?” I said, I do. And she said, “You should ask them about what they say whenever an elder has died in the community.” And I said, “What do they say?” “They say that a library has burned.” Now, I didn’t know this.

Tippett: Wow.

Reynolds: But isn’t that something? “A library has burned.”

Tippett: Yes. Oh, my.

So in the year 2020, before 2020 became 2020, you published this book with Ibram X. Kendi called Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You. It is a — you call it a remix of his book Stamped from the Beginning. When did this book actually get published?

Reynolds: March 8.

Tippett: It was March — oh my God. Really? The week of the lockdown.

Reynolds: In the exact — we were on tour. [laughs]

Tippett: So I think following on what we’ve just been talking about, this book is about ideas, but it’s about what has formed our imaginations …

Reynolds: Correct.

Tippett: … which has formed our lives, which has formed our symbols, which has formed the way we, in granular ways, structure and organize our life together.

Reynolds: Absolutely. I mean, this book is — it’s interesting, because no one’s ever talked about it that way. Good on you, Krista. No one’s ever talked about it that way, I think. I think usually people talk about, well, this is the history of a thing. And it is, but that history is birthed out of the imagination. It literally was conjured up. We’re talking about — imagination is so powerful that it could set forth 400, 500 years of something wrong, which means that it very well could set forth 400, 500 years of something right.

That’s sort of the beauty of humanity. James Baldwin, my famous Baldwin quote, and he has a gazillion, obviously. But my favorite Baldwin quote is, “The interior life is the real life.” The interior life is the real life. “And the intangible dreams of a person may have a tangible effect on the world.” It’s basically saying, what one can imagine, internally, what one can think about when nobody knows, when nobody’s around — one’s secrets — could shift human life. What an amazing thing to think about.

And my role, even with Stamped and remixing — and the reason we called it a remix is because it’s not a YA adaptation, because I actually rewrote the entire book. I wanted — we, he and I both — wanted to figure out how we could tap into the imagination of young people. And when it comes to books around race, or when it comes to history books, usually they are presented to students, not humans.

Tippett: Right. That’s a great distinction.

Reynolds: And I think we wanted to make something the first of its kind, something that was literally made thinking about a 12-year-old or a 14-year-old or a 16-year-old — what they would want to read and how to engage them so that they actually can store new language, new lexicon, new vocabulary, new histories in their personal libraries.

[music: “Lemon Tea” by Gyvus]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Jason Reynolds.

[music: “Lemon Tea” by Gyvus]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with the preternaturally wise, wonderful National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, Jason Reynolds. His award-winning novels for middle grade and young adult readers include Ghost and Long Way Down. And at the invitation of Ibram X. Kendi, he took Kendi’s history of racism and wrote a YA version called Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You.

So basically, just to reinforce what you said a minute ago, this story of race and racism and of us — how it has distorted, shaped and distorted all of us — is just an incredibly powerful, negative example of the power of ideas and words and writing, of turning something into a story that is heard and believed and internalized and lived.

Reynolds: Look, if there’s anything I’ve learned, and if there’s any more of a reason that I am motivated, encouraged to do the work that I’m doing, it’s because I have proof that in the 1400s, it was narrative that proliferated racism. It was narrative that proliferated the idea of a justified slavery, a justified enslavement of African people.

Tippett: You name Gomes Eanes de Zurara as the first racist.

Reynolds: He’s the first racist.

Tippett: It’s not a name I ever heard.

Reynolds: And nor had I, before I read Stamped from the Beginning — as we call it, “Stamped, Sr.” — Gomes Eanes de Zurara, the world’s first racist. But the reason why he’s the world’s first racist isn’t because he’s the first person to believe that African people should be enslaved. That’s not the reason he’s the first racist. He actually was only the scribe. He was the author. He was the one who basically said, “Listen, I have an opportunity to spin the story, because everybody is enslaving people over here in Europe, but the way that we’re going to justify our enslavement of innocent African people is by saying that it is salvific enslavement. It is an opportunity for us to civilize and Christianize the ‘heathen.’ And so I’m going to write a narrative that is expressing that that is what we are doing.” And it is in the writing down of the thing that it is crystallized and then proliferated around the world. He basically twisted it and manipulated it into something that it was not and was able to create justified abuse.

Tippett: Yeah, and when I read your book — and I keep thinking of growing up in Oklahoma, in a small town, and even how we would read about the Trail of Tears, which led to our state, or the history that you’re telling that we all learned about. I mean, there’s a lot of stuff in this book that we didn’t learn, but the Three-fifths Compromise — that five slaves equaled three humans — so that slaves were human and subhuman, and that this was a power play in which both the North and the South participated. [Editor’s note: The Three-fifths Compromise stated that non-free persons were counted as three-fifths of a free individual for the purposes of determining congressional representation, not five slaves equaled to three humans as said here.]

Reynolds: Correct.

Tippett: And we could use so many examples. But I look back, and I don’t know why we didn’t — why were we sitting there? Why were teachers teaching it, and why were we just sitting there, taking it in? Because it doesn’t make sense — I mean, it’s terrible, not just that it doesn’t make sense. It’s awful. It’s absurd.

And you do something in the book, the Stamped book, where you stop at something, and you do a pause — [laughs] a huge pause, like capital letters, bigger font. You do “PAUSE,” you do “TAKE A BREATH,” and you’ll also, sometimes, “UNPAUSE.” And to me, that is a narrative technique, but I almost feel like it’s an offering. It’s almost like a narrative technique we need from now on.

Reynolds: So I’ve had these conversations before, for other books that I’ve written. All American Boys was a book about police brutality that I toured for years and years. So we were having these conversations in person, and so public forums, public spaces, thousands of people, and places that I normally had not been, and my mother would have advised against. [laughs] And what I noticed is that it —

Tippett: And that’s her job, and that’s your job to defy her.

Reynolds: That is her job. And it’s my job to say, “I’ve got to do what I’ve got to do. You raised me to do what I have to do.” But one thing I noticed is the discomfort.

You know, for a long time, if you even said the word “white” in public around white people, you could feel all the air in the room sort of suck out of the room. You could feel — it’s like, we can’t even say these labels that are used just as descriptors. We can’t even say that. So how are we ever going to have a bigger conversation, when I can’t even say “white” and “Black”?

And so I what I wanted to — I understood that, going into the making of this book, and so what I wanted to do was figure out how to eliminate all excuse to backpedal out of the pages. I needed to make sure that no one closed the book. So no matter how heavy the topic was, I understood that there were going to be people who read this, who got so uncomfortable and so vexed over a thing that they did not know that affects their lives — particularly, affects their lives for the positive in ways that they did not know. I didn’t want them to — that human thing that we do, which is defensive. I didn’t want the defense mechanisms to kick in, and then they say, “I can’t read. This is not for me.” So instead I’d say, “Look, let’s pause. Take a break. Take a breath,” as a way to re-center. I’ve watched my mother’s — back in the day, my mother’s meditation circles and all these people — I watched that moment of people being like, “Let’s re-center. Let’s take a second.”

Tippett: You also say “breath-breaks,” breath-breaks and pauses.

Reynolds: “Let’s take a breath. Let’s take a moment. Everyone is still here. We’re all still alive. Everyone’s all right. But we gotta keep moving forward. So take a breath, get yourself together, and we’ll push on” — especially since I’m dealing with kids. I love kids, all kids. I love all the children. At the end of the day, I think that’s our one vested interest. No matter what you think, everybody wants children to be OK. And so in order for me to make sure, again, that I’m being responsible — if I’m going to dump all this information, some of which can be really world-shattering for some people, when they find out some of this stuff — I need to also — for young people, especially — put some mattress there to say, “Look, this is all very true, but I love you. And so let’s take a second. Let’s do a temperature check to make sure that you’re all right, and then we can keep it pushing.”

Tippett: One thing that you’ve said a lot — you’re calling the society and white people to not just focus on the young people of color it is convenient and comfortable to love.

Reynolds: Ah, yes. Recently, I’ve been thinking about this a lot. You hear people all the time, like, “Oh, I’m not racist. I’ve got white friends.” It’s almost a joke, at this point, [laughs] like people — “I can’t be racist!”

Tippett: One thing you said about Thomas Jefferson is —

Reynolds: He’s the father of that. [laughs]

Tippett: He’s the first person who said, “I have Black friends.”

Reynolds: He’s the very first person that ever said he got Black friends. He’s gotta be. But I think that idea that “I’ve got Black friends. I can’t be racist, I’ve got Black friends.” Or I know people who have Black children. “I can’t be racist, I have Black children.” Or “I have a Black partner.”

And the way I always try to explain it to people is, I have so many women friends who — specifically, my heterosexual women friends — who say, “If you want to know how a man is going to treat you, just look at how he treats his mother, and then you’ll know whether or not he’s good or not.” And my reply to that is, “That is ridiculous, because that man sees his mother as exceptional. That’s his mother. [laughs] You’re not his mother.” [laughs] And so when I think about —

Tippett: I’ve said that to my daughter, I will confess.

Reynolds: But think about it. But you’re not his mom. He sees his mom as exceptional, and that is the reason why he treats her the way he treats her. And so when we think about this idea of the Black friend, it’s not that you’re not racist. It’s that you somehow have aligned yourself with who you believe is an exceptional Black person. And that is the problem.

Tippett: And that is not the work.

Reynolds: These are Black people who are convenient for you to love. But the truth is that the kid on your block, the one that you’re scared to walk past, you gotta love him, too. You gotta love him, too. The ones who are locked in juvenile detention centers — unfairly, most of the time, doing hard time, because America has hard time for children, one of the only countries that have maximum security youth prisons — you gotta love them, too. You gotta love them, too. The ones who blast their music coming down your block, and you can’t understand why they gotta turn the music — you gotta push back against everything in you that wants to see something wrong with them and love them, too. If not, then it doesn’t matter how many Black friends you have, it’s a specific kind of Black person that you’re OK with, not Black people. And that’s the difference.

[music: “Pedalrider” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today I’m with Jason Reynolds, the celebrated young writer of books for middle schoolers and young adults, with wisdom for all humans.

[music: “Pedalrider” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I’ve been thinking a lot about rage …

Reynolds: Me, too. [laughs]

Tippett: … and the word “rage,” which is kind of in our public vocabulary, sitting there unsure of itself, but it’s there, and there’s a sense that it’s rightly there. I want to read you some lines from this young man, Danté Stewart, who turned me onto you.

Reynolds: Please.

Tippett: He wrote something in Sojourners about Black rage. He’s a seminarian. He’s a preacher and pastor. “Black rage in an anti-Black world is a spiritual virtue. Rage shakes us out of our illusion that the world as it is, is what God wants. Rage forces us to deal with the gross system of inequality, exploitation, and disrespect. Rage is the public cry for Black dignity. It becomes the public expression of a theological truth that Black lives matter to God.”

Reynolds: Wow. I’m with him. I think we have a hard time addressing rage. And I think he’s right. I think it is a virtue. I think it’s important. I have — one of my best friends in the world, Myisha Cherry, she’s a philosopher. And she writes about the philosophy of anger, the philosophy of rage, the philosophy of forgiveness. And there is something theoretical and theological about rage. And I think we raise our young people to try to avoid it.

And I think — look, I believe that we are — so many people are so scared, for all kinds of reasons, that they are raising young people to not feel their feelings to the fullest extent. And then, when those young people are 25, it’s interesting because then, I believe, that rage becomes reactionary rage and not a conscious rage. Black folks have a right to have a conscious rage — a conscious rage. I mean, Baldwin always talks about it. If you are a Black person who is conscious in America, then you are basically living in a state of anger. [laughs] You are living in a state of anger. It is a conscious and constant thing.

The other thing, though, I will say, the only thing I will add, and not as a pushback but as an addendum, is that if it is not a conscious rage — meaning, if it is not a rage that we can tap into, a rage that exists within the quiver of our lives, along with the joy — then it can very well poison us and overtake us. And it can become an illness. It can cause illness. So reactionary rage is a dangerous thing. But to be able to tap into a conscious rage, I think, is a gift. And I do believe it is a virtue.

Tippett: I’m thinking about the Psalms and how they’re full of, actually, murderous rage.

Reynolds: [laughs] They are. I mean the power of poetry, right? [laughs] The power of poetry. I think rage is — I feel rage now. But one has to know how to wield it. And I think, for me, I choose to put my rage into the energy of helping young people process the world around them. But it comes from a place of rage, and that rage is connected to a love, a true love, an aching love that I have for young people to grow into the people who will push forward freedom and anti-racism and an equitable world.

I think they have it. I think they want it, in a way that we’ve never seen before — I mean, even just the way that they’re thinking about saving the planet. I think that their environmental foresight does not stop with vegetation and atmospheric happenings of the space in which we live. I think it also has to do with all natural elements, including human beings. When they’re talking about environmental change, I really do think that many of them want to change the environment — literally, shift the landscape. That does not exclude humanity. [laughs]

I mean, Krista, if you think about it, if you think about their generation — and I say this often, because I think it’s important — their generation is teased and ridiculed and criticized for being too empathetic, as if that’s a bad thing. And all of us who tease them and ridicule them because they have somehow made our lives a bit more complicated and uncomfortable, because now we have to watch what we say, we have to be careful of — think about that. We have to be careful about making other people feel small, and we’re upset about it. We will have egg on our faces 20 years from now, because what they’re saying is, “We are trying to make an equitable world. We want to make a world where everyone feels safe and free.” And we ridicule them for it. So strange. [laughs]

Tippett: I want to ask you about this, too, because I hear you almost identifying with the oldsters. How old are you — in your 30s?

Reynolds: Thirty-six.

Tippett: Thirty-six. But here’s why. I think — in the ’60s, also, I’ve heard people say this, people said, “Oh, the young will save us.” But what I feel really strongly is, as radical as they are, our young people, we have to walk alongside them. They deserve to be accompanied. And even this move that you help young people make — of stopping and taking a breath — that’s not natural when you’re 12 or 16 or 22. And, actually, that’s part of the strength of being 12 or 16 or 22. It’s that impatience, that holy impatience, that wise impatience. But the history of radicalism — the ’60s just burned out in cynicism. It gave us hedge funds.

And so I do feel like — I wonder how you would talk to the rest of us, who are not identifying as young people, who are looking at that generation and praising them and talking about how amazing they are — oh my God, they have a hard road ahead. We all have a hard road ahead. But what is our work to accompany them towards — I love your word, “fortitude” — so that they can really grow into the fullness of their imaginations and their power?

Reynolds: Fantastic question. So first and foremost, I think there are, like you said, there are some older folks who are encouraging and who are like, “Yeah, go out there and get ‘em.” But I think there are actually more older folks who are like, “Y’all don’t know what y’all doing,” or saying, “All y’all do is buck back.” So to them, first of all, I say, no one wants to live in a world where young people are not irreverent, first and foremost. A world where young people are not irreverent is not a world for me, because it is a world that is not growing. They have to shake the table. If you like your young person’s art and music, your young people are doing something wrong. The truth is that — right? It’s just the natural order of things. It’s the natural order of things. It is their time to mold what they want the world to look like.

So what’s our role, is the question. And our role, I think, in this moment, it isn’t just — I’ve heard people say, “We got to get out the way.” Here’s the thing. I think that they don’t want us out the way. Despite what you may hear, it’s not that they want us out the way, I think what they want for us to do is to listen to them, because I think — what I’ve learned over the years is that when we talk about entitlement, what we do is we say that young people are so entitled, yet I don’t know a group of people more entitled than adults and older people. I mean, we really believe that we deserve their respect simply because we have years on them, and the truth is that that respect must be earned. And I think what they’re saying is, “Please, make a seat for me at the table. You can’t talk about my life and not include me. You have to make a seat for me at the table.”

That is our role in this movement. It’s that simple. It’s like, look, I am here. If you need help, you need strategy planning, you need to understand how this works, you need some historical reference and context, I’m here to do all those things.

Tippett: You need somebody to help you take some breaths …

Reynolds: You need somebody to help you take some breaths, you need somebody to help you make sandwiches and make sure that you all got the proper shoes on, these simple things, and if you’re going to walk into harm’s way, I’m going to pull your coattail and say, “Hey, hey, hey, are we certain? Let’s go over the rules. Let’s make sure that we are doing what we want to be doing.” But if you are emotionally broken, if something happens that hurts you emotionally, then it’s my job to step in and say, “Let’s process what has happened. Let’s figure out where the failure is. Let’s figure out how to grow from it, how to get strong, and then we need to get back out into the street.”

That’s the role of the elders right now, not “Follow me,” not “This is the way I did it,” not “You guys are doing it wrong,” not — no, no, no, that doesn’t work. It’s like, “Look, I’m with you. Tell me what you want me to do. Tell me where you want me to go. If I see the fire coming, I’m going to say, there goes the fire. I’ve seen fire before. Let’s head this way.” That’s it. [laughs]

Tippett: That’s so good. So helpful.

So one thing — as you know, one thing that feels scary for people, for white people right now, is saying the wrong thing. It’s kind of similar to what you just said — we have to make space in our life together to be learning and growing, and that means that people will fail. And we have to find ways to rehumanize and welcome failure that turns into growth.

But anyway, I just want to name, and it feels a little scary to name this, that I get troubled by the language of “anti-racism” as the main word or the main goal, because it’s a negative-negative.

Reynolds: [laughs] That’s great.

Tippett: And I actually — I’m coming to terms with the fact that this is the thing we have to reckon with right now and become, is anti-racist. But it’s not — it can’t be the end. That’s not — so I’m curious what you think about that.

But it also, to me, it goes together with the question I wanted to ask you. One way to describe all of this reflection in the book — in Stamped, but in all of your work — is just opening up this question of what it means to be human, fully human, and seeing that more fully. So how would you start to talk about what it means to be fully human, how that’s evolving in you, and what that has to do with anti-racism?

Reynolds: What does it mean to be human — [laughs] which is like, it’s like being asked, “What’s the meaning of life?”

Tippett: I know. I know. So just how would you start to answer it right now, this morning, on this Monday.

Reynolds: For me, I think it means to be changing. It means to be evolving. I think that’s the part about humanity that excites me the most, is that it’s malleable. It shifts. It changes. The ways of life can change at any given moment, and we can adapt to said ways of life. It means — I always talk about indoctrination. Human beings have been indoctrinated. And so if we’ve been indoctrinated, then that means that we can also make new doctrine and then be re-indoctrinated, I think. And so how it connects to anti-racism is that, in and of itself.

First and foremost, I have to say this. No one is actually — because my friends, my white friends, especially, are like, “Yo, I’m trying to become anti-racist.” That’s not a thing. So I want to make sure that we’re clear.

Tippett: Right, it’s not a thing. It’s to not be a thing.

Reynolds: Not like that, Krista. I know the language is tripping you up. [laughs] What I’m saying is, there’s no finish line, is what I’m saying. There’s no finish line. So there’s no finish line. There’s this idea that people are going to read this book, or they’re going to read all the books, and then, all of a sudden, they’re going to “be” anti-racist. And what I’m saying is — and that’s also a very American thing, this idea that there are winners and losers, that there’s a binary that we live in, a bifurcation when it comes to that which is a failure and that which is victorious.

The truth of the matter is, this is about journeymen, journeyfolk. Our job is to constantly be pressing toward a thing, but that thing is ever elusive. And the reason why it is ever elusive is because the world, and humanity, continues to evolve. And because it continues to evolve, the things that complicate our lives evolve with it. And so we have to be vigilant, to continue to figure out what the new versions of these elements are so that we can continue to tear down that house. But there’s no end goal. There’s no — and I think that’s how humanity and anti-racism connect.

Tippett: So anti-racism is this muscle …

Reynolds: It’s a muscle that has to be developed.

Tippett: … that is with us at every step of the journey.

Reynolds: And it’s simply — and by the way, to get back to your original question, anti-racism is simply the muscle that says that humans are human. That’s it. It’s the one that says, “I love you because you are you.” Period. That’s all. And if we can figure out how to do that — and it feels so simple. And this is why racism has been the greatest hoax ever played on humans. It’s the greatest hoax ever, because that element of “I love you because you are you” should be the most human thing we know. It should be a natural thing to say, “Look, I love you, because you remind me more of myself than not.” [laughs]

Tippett: I really appreciate you, and I’m just really happy that this is how I got to spend this Monday morning.

Reynolds: Me, too. Thank you so much, Krista.

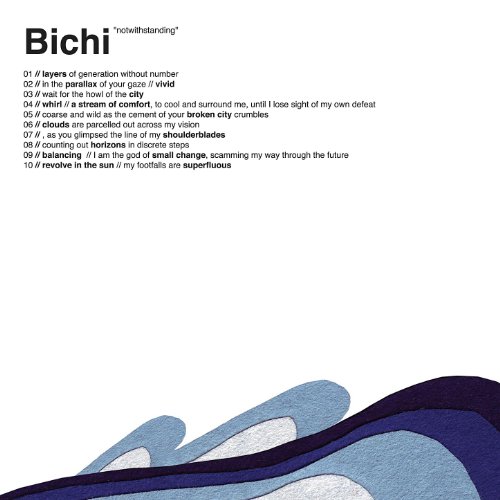

[music: “Revolve In the Sun” by Biche]

Tippett: Jason Reynolds was appointed National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature by the Library of Congress in January, 2020. His many award-winning books include Ghost, Long Way Down, Look Both Ways, and, most recently, Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You.

[music: “Revolve In the Sun” by Biche]

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

The Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

And the Ford Foundation, working to strengthen democratic values, reduce poverty and injustice, promote international cooperation, and advance human achievement worldwide.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections